📘1️⃣ Coding Best Practices#

Let’s address the elephant in the room: many researchers hesitate to share their code, often out of fear of being judged for how it’s written.

While some level of imposter syndrome is inevitable, there are simple, effective habits you can adopt to boost both your confidence and your code quality. These best practices don’t require much extra time, and they can save you significant effort down the line.

Code sharing is no longer a luxury, it’s increasingly expected, made easier by accessible tools and community-driven standards. Open science is gaining momentum, and with it, a welcome shift: code doesn’t need to be flawless to be valuable. In fact, any effort to share code is generally appreciated far more than not sharing anything at all.

In this chapter, we’ll go over a set of practical recommendations, drawn from widely accepted coding standards—that can help you prepare code you’ll feel comfortable sharing.

Not every point will apply to every project, but most will. Aim to adopt the practices that best fit your needs and workflow.

👣 Small Steps Toward Better Coding Practices#

In the ensuing sections, we’ll dive through things you could do make your code better for sharing:

📝 Commenting#

Fig. 3 Comments are essential for making code shareable and understandable.#

Top-level script comments: At the top of each executable script, include a short explanatory comment describing how it should be run. No matter how brief, this should include at least one example of expected usage (e.g., a sample command line call).

Inline comments: Throughout your code, include comments explaining what key blocks or lines are doing. This isn’t just for others—it’ll help your future self, too! 😅

☢️ Variables#

Avoid hard-coding values. Instead of embedding parameters directly into your code (e.g., file paths, thresholds, or flags), assign them to variables.

Centralize configurable parameters. Define variables that others might need to modify, such as input/output paths or settings, at the top of your script. This makes your code easier to read, test, and reuse.

Example

Here’s an example of what not to do:

if p_value < 0.05:

...

A better approach is to define parameters as variables at the top of your script:

# at the top of the script

p_value_threshold = 0.05

# further down the script

if p_value < p_value_threshold:

...

⏩ Functions#

Functions, functions, functions: Functions are reusable building blocks. Break your code into logical, reusable functions wherever possible.

A good rule of thumb: functions should be shorter than a page (~60 lines) and do one thing well.

If a code block appears more than twice, it’s probably worth turning into a function.

🗑️ Eliminate Duplication#

Within your own code: Use functions to avoid copy-pasting logic.

Beyond your code: Don’t reinvent the wheel! Most languages offer high-quality libraries for common tasks. Before building from scratch, check if a well-maintained package already solves your problem.

Fig. 4 The right use of library functions improves not just performance, but also the clarity of your script.#

Warning

🧂 Be cautious when using new or experimental packages. Test imported functions before integrating them into your workflow.

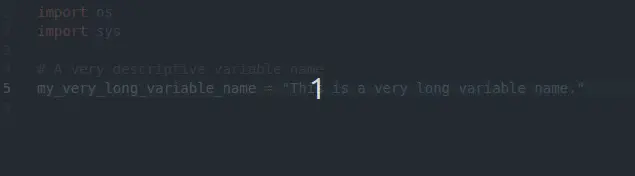

Fig. 5 When in doubt, opt for descriptive variable names over short but ambiguous ones.#

💬 Naming Matters#

Use meaningful names: Choose descriptive names for variables and functions. The broader their scope or importance, the more informative the name should be.

For loop counters, short names like

iorjare fine.For important variables or data structures, avoid cryptic one-letter names.

Tip

Tab Completion: Most modern text editors support tab completion, so long, descriptive names don’t slow you down!

Fig. 6 Tab completion facilitates using long, descriptive names without slowing you down.#

📦 Dependencies#

List script requirements: Include a

requirements.txtfile (or equivalent) to specify the dependencies needed to run your code.Alternatively, create a Getting Started section to your project’s

READMEfile with clear setup instructions.

⚠️ Avoid Commenting Out Code#

Don’t toggle code behavior by commenting and uncommenting blocks. Instead, use

if/elsestatements, configuration files, or flags for control flow.

Fig. 7 Avoid using comments to toggle code on or off—there are better ways.#

🗂️ Archive Your Code#

If you want to make your code citable and discoverable, consider archiving it on a DOI-issuing repository. Zenodo integrates seamlessly with GitHub, allowing you to create a citable snapshot of your project.

For further reading, you could check out the following resources:

Open and reproducible neuroimaging: From study inception to publication [2]

The Turing Way’s Guide for Reproducible Research

Best Practices for Writing Reproducible Code, an online course by Utrecht University.

British Ecological Society’s Guide for Reproducible Code